Imphal, June 22, 2025

A 230-year-old British diplomatic account has resurfaced as a powerful historical rebuttal to ongoing claims that Kuki communities are “recent settlers” in Manipur.

The account, written by British envoy Major Michael Symes in his 1795 publication “An Account of an Embassy to the Kingdom of Ava”, offers what many historians now call irrefutable evidence of Kuki habitation in the region centuries before Manipur’s modern boundaries were drawn.

In the account, Symes describes an expedition led by Captain Swinton in 1763 to a region called Mackey, surrounded entirely by what he terms the “Cookie mountains.” Symes wrote, “In the spring of 1763, Swinton was placed in command of an expedition to Mackey, which he describes as a hilly country, bounded on the north, south and west by large tracts of Cookie mountains and on the east by the Burampoota; beyond the hills to the north by Assam, to the west Cashai (Cachar).”

To many scholars and tribal historians, this single paragraph is a bombshell, challenging decades of politically driven narratives that seek to question the legitimacy of the Kuki people in Manipur. “The British had no stake in our identity politics. Symes was simply recording what he saw. And what he saw was a well-defined Kuki territory long before the modern state of Manipur was even conceptualized,” said Dr. L. Doungel, a tribal historian based in Churachandpur.

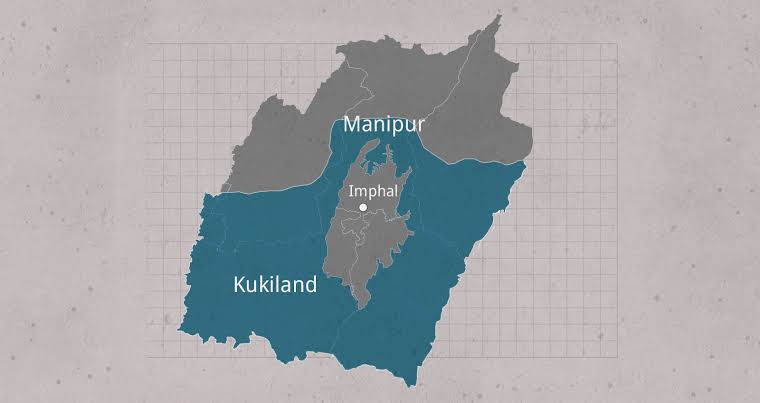

The phrase “Cookie mountains” — the 18th-century colonial spelling of Kuki — confirms not only territorial occupancy but also political control. It suggests that the hills surrounding the Imphal valley were ethnically, geographically, and militarily associated with the Kuki people as early as 1763 — nearly a century before the British formally recognized the Manipur state boundary in 1894.

The implications are particularly timely. In a recent rebuttal to former Chief Minister N. Biren Singh’s memorandum accusing Kukis of being illegal immigrants, the Kuki Organisation for Human Rights Trust (KOHUR) cited Symes’ account to counter claims of demographic invasion. “When Symes spoke of Kuki Hills surrounding the valley in 1763, there was no Manipur as we know it today. This proves that Kukis are not outsiders — they are the original highland dwellers,” said H.S. Benjamin Mate, Chairman of KOHUR.

Symes’ diplomatic mission had nothing to do with Manipur’s internal politics, which strengthens its credibility as a historical source. “His references to ‘Cookie mountains’ were not political statements — they were geographic facts. The British did not invent the Kukis; they recorded them,” added Dr. Doungel.

The narrative around “Kuki Hills” gained further prominence during British colonial rule, particularly after the Kuki Rebellion of 1917–1919, during which the British officially designated the surrounding hills as “Kuki country” in their intelligence reports. By 1901, British census records already documented Kuki populations and their settlements across present-day Churachandpur, Pherzawl, and Chandel — many of which were excluded from earlier colonial censuses, making modern comparisons misleading.

What Symes’ account ultimately establishes is that Kuki territorial identity long predates not only Indian independence but also the formal creation of the Manipur state. While political actors today weaponize census data and colonial maps to serve contemporary agendas, the words of an 18th-century British officer continue to ring with inconvenient truth: the Kuki Hills were always there — long before Manipur had borders to argue over.

As debates over indigenous identity continue to dominate Manipur’s volatile politics, Symes’ 1795 account stands as both a historical document and a moral compass, reminding policymakers and the public alike that truth is not built in a day — and neither are communities.